Grammar paranoia is what keeps copy editors like me well-fed. Our clients know that they need to present themselves professionally, and they might also know that they don’t have the ability to craft sparking, error-free sentences unless they get a little help. So they hire copy editors who can polish their copy and otherwise help them communicate clearly in any written format.

Sounds great, right? Unfortunately, I’ve found that a number of my clients simply don’t understand what copy editing really is, and similarly, many of them become remarkably defensive (or even downright combative) when I’m trying to do my job.

Client education

While client education isn’t technically part of a copy editor’s job, working with clients who have a firm grasp of the scope of work, and the value of that work, tends to translate into projects that don’t raise my blood pressure and that do blossom into repeat assignments. Here’s how I make it happen.

In the hands of an inexperienced client, the words “copy editing” could encompass everything from headline writing to hard edits to proofreading. Without a firm definition of what it is you’re supposed to do, you could either do much more than your client expects, or you could leave that client wanting much more than you’re prepared to deliver.

In a perfect world, your client will send you a page or two of the documents you’ll be working with, or a link to a few online samples. That data is a great tool for client communication, as you’ll quickly see if the documents in the queue are really ready for copy editing.

I’ve had a few clients send me projects that clearly needed substantive editing, not copy editing, and I was able to provide those services and then move on to copy editing. These projects were missing entire sections, the logic of the piece was a little fuzzy, and it seemed as though some of the work wasn’t coming from a native English speaker. This requires substantive editing (Substantive editing usually involves analyzing and/or restructuring a document for substance and structure from the headline through to the ending. Substantive copy editors help clients specify their objectives, their readership, and the arrangement of the content.), and fixing it would have cost me quite a bit of time, and the fees should be adjusted accordingly.

A sample is vital in helping you find these problems, but if a sample isn’t available, clear communication can save you. I like to nail things down in a formal scope-of-work letter. Here, I attempt to outline what sorts of work I will do, and what sorts of things might prompt the client and I to reassess the project as a whole.

My typical letter sounds something like this:

As I work, I will be looking for and correcting these sorts of problems (in no particular order):

- Typographical errors

- Awkward sentence structure

- Missing words

- Misplaced punctuation

- Broken links

- Misplaced artwork

- Missing page elements

- Inaccurate source attribution

- Overlong paragraphs or sentences

- Missing subheads

- Lack of consistency among documents

- Repeated words

In general, I won’t be checking the arguments the piece is making, the legality of the arguments or providing comments about how the piece should be developed, structured or shared. That’s a very different form of editing, and I’m happy to provide it, but we’ll need to talk again if that’s the sort of work you require.

The importance of being firm

It might sound persnickety, but it’s best to be firm in the beginning of a contract negotiation. There’s no money on the table or lost work to recoup at this stage, so there’s very little at risk. Being firm now can make a lot of sense.

Proofreading

Some clients send along Word documents that you can edit using your own computer. But, some clients will ask you to work with sensitive, proprietary information that simply can’t be passed from one computer to another. If this is the case, you might be asked to write all of your corrections down, and your client will make your amendments for you. If you’re working in sensitive fields like engineering or manufacturing, this is remarkably common.

Those of us who work in the field know proofreading marks backwards and forwards, and it can be easy to forget that many of our clients have no idea what our scribbles mean. In addition, it’s easy enough to develop a few quirks in your own proofreading markup style from one day to another, if you’re accustomed to making your own changes.

At the beginning of a project, I print out two sets of proofreader’s marks (I use the set provided by Merriam Webster). I keep a copy for myself, and I set one aside for my client. I refer to those marks as I trot trough the pages, and when my work is done, I send that key along, so my clients know what in the world I want them to change.

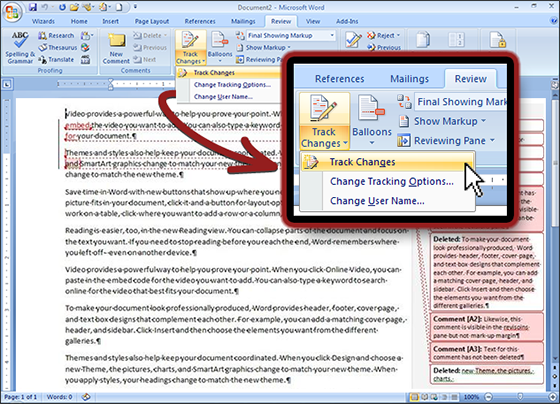

If I’m working in Word, I use the track changes function, and I always delete text first and then add replacement text. When I’m done, I also take a pass through the document as though I’ve accepted all of the changes, just to make sure I’ve introduced no formatting errors. Some clients simply accept everything without looking at your edits, so you simply must be sure that your final document is clean. It also pays to provide step-by-step instructions on accepting tracked changes, as some clients have no idea how these tools work.

MS-Word has a feature that lets you track all editing changes

Only edit what you need to

Many of us who provide copy editing services also write on the fly, and if you’re like me, you have a very specific voice you employ in your professional work. When you’re working on pieces of your own, it’s perfectly appropriate for you to make edits that are based on your gut. Swapping out words, shifting sentences and otherwise tweaking copy might seem “right” to you, as it puts the document in line with your voice. However, these little steps can absolutely stomp on a writer’s sense of ownership and creativity. As I work, I prepare to defend each and every edit I make. If I can find a reason for changing something by consulting a dictionary, grammar resource or style book, it gets changed. If I cannot defend that edit, the original text stays. This helps me to respect my clients, and it also helps me to avoid arguments I simply can’t win.

There are times, however, when this rule can have a little flex. Sometimes, for example, a sentence might be technically correct and yet it might still grate the ears.

If I cannot live with myself unless I change it, I add in buffer words to my edits, such as “You might” or “Consider.” That allows the writer the freedom to either accept your suggestions or leave the text in its current form. That little nicety might keep that client coming back to you in the future, while saving your professional pride.

After you’re done

When my work is complete, I don’t simply slide my markups back to the writer with a bill for my time. I also create a sort of cover sheet that summarizes the sorts of changes I suggested, along with compliments about the work the writer has done. It’s a nicety that allows me to smooth the moment at which the writer sees my comments, and it also allows me to give writers a few tips they might consider employing in any writing they do in the future. Again, that might lead to repeat work down the line.

Communicating with clients in this manner might seem like a hassle, but it really can help you to develop conflict-free relationships that translate to a robust workload. To me, that’s well worth the effort.

About the author:

Jean Dion has done an extensive amount of copy editing and proofreading for the engineering industry, and she’s done substantive editing for many healthcare companies. Jean is also a prolific writer. She’s discussed responsible pet ownership and pet health care on her own blog, and has written about reputation management, finance, gardening, employment and health care for her clients. Jean’s work has appeared in the Search Engine Journal, Tweak Your Biz and Under 30 CEO, and several magazine pieces are currently in development.